Asian Elephants

The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) is found in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia (Sumatra), Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam. It comprises three subspecies – Indian, Sumatran, and Sri Lankan. Though smaller than their African cousins, Asian elephants are still the largest land mammal on the continent. They have proportionately smaller ears, and only some males have prominent tusks.

Asian elephants are under severe threat and declining rapidly in numbers. They have been listed as endangered by IUCN since 1986, and their population has declined by at least 50% over the last 60–75 years. There may be as few as 40,000-50,000 remaining in the wild.

The main threats to the species are loss and degradation of habitat due to increasing human population, agricultural encroachment, human-elephant conflict (HEC) and capture for entertainment and tourism purposes. Poaching remains a significant threat to the already small elephant populations in Asian countries, with tusked males hunted for their ivory; there is also a strong demand for other elephant body parts, including their tails, skin, hair, and meat.

There are around 15,000 captive Asian elephants. Their lives are ones of unremitting suffering. All elephants in tourism have one thing in common: they have all been tied up and beaten to the point where they will submit to humans, in a process known as phajaan (‘the crush’). They are routinely tortured to keep them obedient and submissive.

Please, never ride an elephant, visit a show or a temple that uses elephants, or support street begging with elephants. Only support ethical experiences!

Covid-19 Hit Elephants Hard

In Thailand, when the borders closed to tourism for two years from March 2020, elephant owners saw their source of income dry up completely. They couldn’t afford to pay mahouts (elephant carers) so elephants were chained to the spot 24 hours a day, with no exercise and limited food and water. Chained elephants could be seen swaying, a sign of extreme distress. Many died of starvation and neglect. With no other choice, many owners took their elephants home to their villages, where they struggled to feed them. For the owners, the situation is improving as tourists return to Thailand; for the elephants, many returned to the riding camps, and other commercial work that keeps them in chains.

Video of elephants affected by the pandemic in Thailand

In India, many captive elephants also faced starvation during Covid.

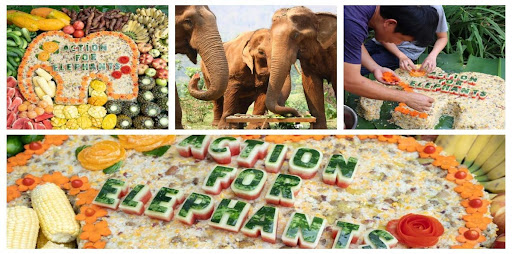

A Great Way to Help Thailand’s Elephants – Elecakes!

You can buy a beautiful cake made from fruit and vegetables for the sanctuary elephants to enjoy. Each cake is designed with great skill and care by dedicated staff, and not only makes a unique gift for your loved ones but also helps to feed the elephants and give their owners an alternative income. You’ll also get a video of the elephants enjoying their delicious treats!

You can purchase cakes from Gentle Giants, Asian Elephant Projects, Samui Elephant Haven, and Chok Chai Elephant Park for elephants in Thailand.

Cake made by Care for Elephants at the Asian Elephant Projects

Cambodia’s Elephants

A healthy Asian elephant population that can be expected to survive in the long term must be made up of at least 500 individuals. In Cambodia, the total number of wild elephants is estimated to be between 400 and 600, with different groups scattered across two main areas on opposite sides of the country, each home to 175—300 individuals. A handful of much smaller populations exist in other areas of Cambodia. There are around 75 captive elephants.

These low numbers are due to habitat loss and fragmentation caused by expanding agriculture and infrastructure development – also human-elephant conflict, poaching, live capture, and human disturbance (such as the use of existing roads which cut through elephant habitat).

Ethical experiences:

Cambodia Wildlife Sanctuary

For day visits you can contact via their FB page

Blog: how to find the kindest elephant sanctuary in Cambodia

Organisations supporting elephants in Cambodia:

India’s Elephants

India is home to over 55% of the Asian elephant population, with approximately 27,000 elephants in the wild. As the human population grows (India became the most populous nation on earth in 2023), the elephants’ habitat is shrinking, putting them under immense pressure; with their ancient corridors and routes blocked by human development, their resources are cut off and they are pushed into contact and conflict with humans. They destroy crops and often venture into villages looking for food. There are fatal collisions with trains that speed through wildlife areas, and frequent deaths by electrocution from unauthorised fences. Indian elephants face many struggles to survive.

Between 2010 and 2020 a total of 1,160 elephants were killed in India by non-natural causes. Electrocution due to contact with power transmission lines accounted for more than half of the deaths, with 348 elephants dying this way between 2017 and 2022. Another 186 jumbos lost their lives on railway tracks, followed by poaching, poisoning and train related accidents.

Another very worrying statistic is only 4.4% of the remaining 27,000 elephants in India are male.

Elephants used in festivals and temples

Elephants are used in temples across India, mostly in southern India and especially concentrated in the Kerala region (it’s estimated there are nearly 450 captive elephants in Kerala alone). Many are stolen from the wild and are predominantly male. They are often owned by the temple, and the more prestigious temples will normally have at least one elephant. The elephants are kept in camps in hellish conditions. There is no compassion or veterinary treatment for them, and scars or injuries sustained through abuse are left to fester and worsen.

The elephants are usually used for religious ceremonies and festivals that take place during the hottest period, from December to May. They are draped in a caparison (ceremonial robe) and a solid gold mask and made to stand in the heat for hours on end, with open wounds and massive ulcers, their chains so tight that they cannot even put their legs properly on the ground. After the festival is over, the elephants will face a long walk to the next festival or be placed on the back of trucks, with no shade or safe structure.

The documentary ‘Gods in Shackles’ exposes the brutality these temple elephants endure.

Most of the elephants are bulls, and although musth (a periodic condition in bulls when they experience highly elevated testosterone levels) usually occurs in winter months, it has been known for elephants to participate in ceremonies and festivals during this musth period. They are intentionally starved and given no water in order to deplete their energy and delay their entering musth. After their musth, the elephants are repeatedly beaten by up to six men; there’s a myth that after the musth cycle the elephants have forgotten their commands, so their mahouts (trainers) beat the elephants to reinforce their control. Some beatings are so severe that the elephants die.

Due to the elephants’ extreme suffering during festivals, and the abysmal living conditions forced on them, bulls have been known to retaliate aggressively, sometimes resulting in human fatalities and casualties.

Elephants waiting to give rides to tourists at Amber Fort

Elephants are used to carry tourists to the Amber Fort in Jaipur in the scorching sun. They are given no food or water while working. When they are fed, the food is nutritionally inadequate, barely fuelling them for the steep slope they have to climb in the blistering heat. They are forced to walk over concrete surfaces which cause them pain and distress.

The majority of elephants are kept in private sheds with no facilities to cater for their basic needs. They suffer from infections, back swelling, foot pain, skeletal deformities and psychological distress and depression.

Begging elephants

Elephants are used for begging on the street in many places in India and Thailand (though illegal). They fare no better than any of the other animals used for entertainment purposes and suffer the same barbaric treatment and lack of care. They are usually chained and controlled through the infliction of pain or threats of it. They are not fed sufficiently, are dehydrated and forced to work long hours without rest or shelter. Walking all day on hot concrete causes painful damage to the sensitive pads on their feet. Animal retaliation, when the elephant can no longer endure the suffering and lashes out, can also occur, often with fatal consequences.

Ethical experiences

In the whole of India there is only one small ethical sanctuary (Wildlife SOS) where one can visit elephants. We recommend that people see elephants in the national parks, where they are wild.

Organisations working to help India’s elephants:

Robot elephant: a humane alternative

A marvel of technology and artistry, the robot elephant called Irinjadappilly Raman is almost indistinguishable from a real elephant. Its use at festivals would spare sentient and sensitive beings a life of misery.

The Irinjadappilly Sree Krishna Temple in India has pledged not to keep or hire live elephants – or any other animals – for events ever again. ‘Robots like Irinjadappilly Raman are a kind and safe option to help replace the inhumane practice of chaining and beating majestic animals into submission,’ said PETA India, which donated the robot.

UPDATE – Nov 2023

Following the success of the Irinjadappilly robot elephant, eight more temples have signed agreements with PETA to acquire one. Four of those temples are in Kerala, three are in Tamil Nadu, and one in Karnataka, while the Mudikkannur Sree Krishna Temple in Thrissur district has also asked for one. Hopefully this trend will continue and the suffering and cruelty endured by elephants used for festivals and parades will come to an end.

Laos’s Elephants

Once called the land of a million elephants, today Laos has only around 400-700 wild elephants left, and 400 in captivity.

Deforestation is the root cause for the decline in wild elephant numbers in Laos, due to demand for timber in neighbouring China and Vietnam. Laos has about 40% of forest coverage today, down from 70% recorded in the 1950s. As the forests diminish, it leads to habitat fragmentation, and the elephants are unable to follow normal migration patterns. This leads to crop raids and human-elephant conflict.

Elephants in captivity have a bleak outlook. They are dying as a result of being fed unhealthy diets and forced to work in poor conditions at elephant tourism camps, or due to injury and neglect.

Their numbers are rapidly decreasing; many are sold or rented abroad – Korea, Japan, and China are common final destinations which give a good income to the owners.

As with other elephants across Asia, elephants in Laos go through the brutal training process known as phajaan, where they are beaten until their spirit is broken and they obey humans. This is normalised in Laos, where the whole village will come to witness this tradition of ‘taming the elephants’, where the animal is tied up and tortured for days.

If the current trajectories continue, it is projected that there will be no elephants left in Laos by 2030.

Ethical experiences:

Save Asian Elephants Foundation – Laos

To book to volunteer, you can email sef@saveelephant.org or go to their FB page.

Myanmar’s Elephants

Myanmar has the second largest population of Asian elephants (after India), with 4,000–5,000 in the wild and over 5,500 in captivity. Most of them work in the logging industry; 3,500 of these elephants are owned by the Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE), which brands the elephants with an identification star and number. Over 2,500 elephants are privately owned. The country has the largest population of captive elephants in the world. They will all have been through the ‘crush’, to break their spirit and render them obedient.

There is the political will now to reduce logging, which will create a situation of excess out-of-work elephants in Myanmar. MTE has a duty to take responsibility for the elephants’ care, but reduced logging will mean MTE will need fewer elephants. The sector that will need help is the one of privately owned elephants. The recent requirement has been to reduce their elephant population in a systematic way and create job opportunities. Currently captive elephants are allowed to mix with wild elephants in the forests at night and breed.

With Covid-19, and the state of emergency declared when the military took control of the country in February 2021, the fate of Myanmar’s logging elephants is uncertain.

Organisations helping logging elephants in Myanmar:

Nepal’s Elephants

Often forgotten, Nepal’s elephants number approximately 120 in the wild and 208 in captivity.

Of those in captivity, 92 belong to the government and the rest are used in tourism. The government-owned elephants are bred to patrol the national parks. There are several government facilities, the most notable being the elephant breeding centre in Sauraha, Chitwan. When the elephants are not patrolling, they are kept on chains. The female elephants are continuously having calves as wild bulls are allowed into the facility to mate with them. The females are chained so have to endure this forced breeding and further suffering when their calves are taken away.

The baby elephants born in the breeding facility stay there until they are broken at around 4 years old. They are then dispersed through different locations. Each national park has army bases throughout with elephants stationed there, plus there is a bull elephant facility in Sauraha where several of the large bulls live.

Each female is kept under a shelter with her calf until the baby is ‘trained’ – subjected to pain and torture until its spirit is crushed. While at the facility, the elephants are unable to reach other elephants, and sometimes even their own calves are kept just out of reach. When they’re on patrol in the jungle they are able to socialise with one another.

All the government elephants are used for patrolling the national park during the day and some (especially the bulls) are used for conservation activities like tiger captures and wildlife censuses. The elephants generally go into the national park in the morning for a few hours so the mahouts can cut grass, after which they return to their shelters where they’re chained while the mahouts eat. After, they head back to the national park to patrol. During this time the elephants are mostly grazing and making their presence known to any potential poachers or unauthorised people in the park. They remain in the park grazing from about 10 am to 3 pm, then return to their respective facilities where they are chained until the next morning.

Many of the government mahouts have started using axes instead of bullhooks to manage the elephants (especially the bulls or dangerous females), which you don’t see with the privately owned elephants. There are many mahouts who care for them though, and because the government mahouts get paid a much better salary with benefits, they generally work hard, and fewer have issues with alcoholism.

Privately owned elephants are not permitted to enter the national park, so most are chained when not giving rides and have very little reprieve.

You can read more here about Nepal’s wild elephants and the threats they face.

Illegal import and forced breeding

Because breeding of captive elephants is expensive in Nepal, old, sick, or diseased elephants are frequently imported illegally from India and used for trekking and tourism.

Many tourists go to Nepal wanting to experience an elephant ride, not realising that every ride contributes to the harsh treatment, forced breeding, and exploitation of Nepal’s elephants.

Organisations working to help Nepal’s elephants:

Sri Lanka’s Elephants

The population of wild elephants in Sri Lanka according to the IUCN Red List is reported to be 2,500 to 4,000; other sources report as high as 7,500, but there has not been a census since 2011 to confirm these figures. More elephants and humans die in Sri Lanka due to human elephant conflict than anywhere in the world. Below are the figures for deaths of elephants and humans reported by RARE, an animal rights advocacy organisation in Sri Lanka.

2017 – 256 elephants/87 humans

2018 – 319 elephants/96 humans

2019 – 407 elephants/122 humans

2020 – 328 elephants/142 humans

2021 – 375 elephants/142 humans

2022 – 439 elephants/145 humans

2023 – 476 elephants/169 humans

Conservationists are extremely concerned for the future of wild elephants in Sri Lanka unless effective measures are urgently adopted.

The land mass in Sri Lanka is far smaller than other elephant ranges and the elephant density higher. Land is taken for development and agriculture, pushing elephants into small pockets of land with fewer available food sources; this causes them to enter villages and farmers’ fields to seek food, leading to more human elephant conflict (HEC).

To stop wild animals from raiding their fields, farmers make a fruit bomb known as hakka patas (‘jaw exploders’), with explosive matter, lead, and iron made into a ball, which is inserted into a pumpkin or other fruit and left out for the animals raiding their crops. The bomb will explode in the elephant’s mouth, leaving it unable to eat or drink and facing a slow and agonising death.

In February 2021, farmers in Sri Lanka staged a 70-day hunger protest calling for the government to protect land for the elephants so they would be able to stay in the forests to find food and not venture out into the farmers’ crops. In April 2021 the government declared the establishment of the Hambantota Managed Elephant Reserve and previous to this, in 2020 a national action plan to mitigate human elephant conflict was devised by eminent conservationists. To date, the Sri Lankan government had failed to implement either plan, and people and elephants continue to be killed at an alarming rate.

Captive elephants

There are around 200 captive elephants in Sri Lanka; approximately half are in government-run zoos and the other half are in private ownership (by the wealthy and politicians) or temples. Elephants are used in tourism, in temples, and in traditional Sri Lankan festivals called peraheras. Viewed as status symbols, they are also rented out to riding camps.

The perahera

Most temples in Sri Lanka hold an annual perahera festival, in which the elephants are caparisoned in heavy costumes covered in electric lights and are forced to parade in chains through the streets for hours amid flaming torches, beating drums, and loud music. The largest and most famous perahera is the annual ‘Candy Esala Perahera’ which continues for 10 consecutive days with up to 80 elephants paraded each evening. Their use in such festivals causes elephants severe distress and they often run amok, causing damage to property and injuries (and sometimes fatalities) to spectators.

Elephants in temples and private ownership

When not being paraded, most elephants remain chained to one spot in the temple premises or owner’s garden. Often they have no available water source and are left standing in their own waste for many hours; they suffer from lack of free movement, lack of enrichment, and have virtually no opportunity to socialise with other elephants. As with all captive elephants used for rides or performances, they are beaten until they learn to submit to human commands. Stereotypical behaviours are often seen in these elephants, caused by stress, distress, boredom, or frustration.

Despite the poor care offered to elephants in private ownership, some of the country’s religious leaders, along with the pro-captivity lobby, are calling on the government for more elephants to be captured from the wild to be used in festivals and temples.

Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage

This venue was founded with good intentions as a site to care for orphaned wild elephants, but over the years has become a tourist attraction and elephant abuse hotspot. Pinnawala hasn’t acted as an orphanage for many years; calves seen here nowadays are the result of captive breeding. All elephants at Pinnawala are chained and managed by old-fashioned domination and fear-based tactics using the cruel bullhook. Pinnawala even sends some of their elephants to take part in peraheras.

Video of elephants used in Sri Lanka’s perahera festival

Until tourists stop paying to ride them, elephants will continue to face exploitation and abuse. If you’re visiting Sri Lanka, please refuse to ride elephants, avoid visiting any attraction that offers or endorses elephant rides, and steer clear of festivals in which elephants are paraded. This includes the Pinnawala Elephant ‘Orphanage’, Dehiwala Zoo, and Kandy Esala Perahera festival.

The only facility in Sri Lanka that is close to ethical is the Elephant Transit Home, a halfway house for orphaned elephants. After rehabilitation, the elephants are released back into the wild, many into the Uda Walawe National Park. Although you can’t get up close and personal with the elephants, you can observe them at feeding time from a viewing platform. Elephants here are not normally chained at night (unlike at other elephant ‘orphanages’ in Sri Lanka). Over 100 elephants have been rehabilitated at the Elephant Transit Home and subsequently released into the wild. Around 40 or so juvenile pachyderms are usually here at any one time. Most tour operators include a visit to the Elephant Transit Home in their trips.

Organisations working to help Sri Lanka’s elephants:

Centre for Eco Cultural Studies (CES)

Sumatra’s Elephants

Sumatran elephants are a subspecies of Asian elephants, one of the two elephant species in the world. In 2012 they were listed as Critically Endangered and are thought to number only around 1,700 in the wild, living in 25 fragmented habitats on Sumatra.

Their decline is due mainly to habitat loss, fragmentation, and human-elephant conflict, as well as being poached for their tusks. Over two-thirds of the elephants’ lowland forest has been lost to widespread deforestation, and almost 70% of their habitat has been destroyed in a single generation. This has resulted in localised extinctions in many parts of the island, a trend that will continue until they are all gone unless action is taken to save them. The loss of genetic viability due to the elephants’ decline in numbers and loss of their natural range is another driver of extinction.

It is thought there are around 700 elephants in captivity, held in ‘conservation response units’ (CRUs) or in local tourist attractions. There is no management strategy in Indonesia and the care of captive elephants is not monitored. But knowing how captive Asian elephants are treated elsewhere, it’s not hard to imagine the dire conditions and suffering endured by these elephants.

The Sumatran Elephant Project aims to make welfare assessments at all CRUs across Sumatra, with the hope of developing a management protocol that can be set up at these centres to ensure high welfare standards and improved management for all of the captive elephants.

Thailand’s Elephants

Thailand has approximately 3,800 elephants working in the tourism sector, and only around 3,000-3,500 in the wild. In 1989, a sudden ban in logging, an industry that used elephants to haul heavy felled trees, left lots of captive elephants out of work, with no income for their owners, so they were put to work in the tourism sector. As tourism boomed, so did the call for elephants used in the industry, giving rise to riding camps, having elephants perform for tourists, putting baby elephants on display for tourists on beaches and in hotels, and sanctuaries falsely claiming to be ethical. Never support or pay for these elephants’ exploitation.

Breaking the spirit

All baby elephants captured from the wild or bred from captivity will be ‘trained’. This is a very brutal and cruel process. The baby is taken from its mother and moved to a very small space – a wooden cage or a hole – and tied tightly so it will be unable to move throughout the whole process. This ancient tradition of torture is called phajaan, which means ‘breaking the spirit’ (also known as ‘the crush’).

While wild elephants are protected, domesticated elephants are not. They are classed as cattle and have no protection in law. They are used in illegal logging and tourism. All domesticated elephants go through phajaan.

Once the elephant has been broken, it will be used to give tourists rides and perform demeaning tricks, such as painting, bicycle riding, tightrope walking, and playing basketball, all of which are of course unnatural behaviours. If they make any mistakes, the elephants will be punished after each performance. When they’re not out performing or being ridden they’re kept chained in place.

Signs of change

In recent years there has been some positive change, and camp owners are moving away from riding camps to observation-only experiences. But many camps still allow bathing, making the elephants do multiple bathing sessions in one day and forcing them to stay in the water. Also, the elephants are often tied when tourists have gone or not in view. Other camps are still in transition from their previous riding set-up, and although they have moved away from riding, do allow some forms of bathing – this may be one encounter a day and the elephants are free to move out of the water at any time. However, there is always a risk of being in the water with a large animal which, like with any animal, could be startled at any time.

Ethical observation-only experiences:

Organisations working to help Thailand’s elephants:

Vietnam’s Elephants

The elephant population of Vietnam has been declining since the Second World War for similar reasons found in the rest of Asia: deforestation, habitat loss, and poaching. But in Vietnam, decades of conflict and warfare hastened the decline even further, as a result of bombing, landmines, and poisoning with Agent Orange, napalm, and other defoliants. Today, there are only around 100 wild elephants left, and approximately 88 in captivity.

Deal to ban elephant riding by 2026

Organisations coming together to save Vietnam’s last elephants

Never ride an elephant – its life is one of torture

Elephant rides and trekking camps are common in Vietnam, Nepal, Cambodia and particularly Thailand. In Thailand, elephants had been used in the commercial logging industry for centuries. When this process was outlawed by the Thai government in the late 1980s, it left thousands of elephant owners without an income. This void was quickly filled by transferring the animals to trekking camps to provide rides and other forms of entertainment (tricks, painting, football, swimming, etc.) for tourists.

Despite their size and strength, elephants are not physically equipped to have people on their backs; riding elephants will result in painful arthritic conditions which do not occur in wild animals. The only reason they submit to such agony is because they all went through phajaan, a process that beat them into submission.

Life for elephants at a trekking camp is filled with physical abuse, beatings, hunger, dehydration, and enslavement in chains. Animal retaliation is another consequence of abuse, which these elephants share with their counterparts in India’s temples, often with fatal consequences. In Vietnam in 2015, two elephants dropped dead of exhaustion with tourists on their backs (no tourists were hurt on these occasions).

As long as tourists keep riding elephants, the suffering and torture will continue. There are alternative ways for the owners to derive income from elephants, and it’s hoped that more and more of them will convert to the observation-only approach for visitors.

Don’t get duped – what to look out for when planning your visit

It is clear that many elephant experiences are unethical, horrifically cruel, and potentially fatal. But thankfully there are many dedicated groups working to rescue these poor, abused creatures and provide them with a better life. Many of these groups provide ethical tourist choices and the opportunity to get close and interact in a responsible manner with elephants.

It is very encouraging that so many dedicated people are offering an ethical alternative for elephant experiences. Unfortunately, there are still many experiences that claim to be ethical and compassionate towards their animals when this is nowhere near the reality. But there are some tell-tale signs that can help to ensure that visitors make an ethical and responsible choice.

Read reviews by other visitors. Be aware that just because a place calls itself a sanctuary doesn’t mean it’s an ethical establishment. As a rule of thumb, the purpose of a proper sanctuary is to ensure that elephants live a life as close as possible to the one nature intended, with minimal interaction with humans. If you see that the animals’ welfare is prioritised over pandering to tourist entertainment, the chances are you’re in the right place.

When choosing an elephant experience, please look out for these signs of abuse:

- Riding elephants, or other unnatural contact such as sitting on their heads, necks, trunks, or hanging off their ears

- Chained animals

- The use of a bullhook or any other instrument to inflict pain, such as nails, sticks, blades, etc

- Baby elephants without their mothers. Often baby elephants are flaunted in hotels and on beaches, where they’re trained to ‘frolic’ in the water to entertain people

- Unnatural settings, such as towns and cities

- Adorned animals, such as ceremonial dress, paint, and masks

- Unnatural behaviour, such as painting, playing football, massaging, and performing tricks

- Coercion or aggression towards the animal if it does not perform as instructed

- Bobbing and weaving behaviour by the elephant – this is caused by stress due to captivity

- The condition of the animal, such as scars, wounds, malnutrition, and bones showing; or often just the look of suffering in their eyes

Human-elephant conflict

The biggest threat to Asian elephants is loss and fragmentation of habitat. Asia is the most populous continent on Earth, and India the most populous country, and elephant populations are being squeezed inexorably by human expansion and development. With their forests razed, lands built upon and migratory routes blocked, wild elephants are forced to seek food elsewhere, bringing them into conflict with human communities. These encounters can involve the destruction of crops and property, as well as human injury and death; in turn, humans retaliate against elephants, often lethally.

In India alone, every year 100-300 people and 40-50 elephants are killed during crop raiding. In Sri Lanka, 327 wild elephants were killed in 2020, rising to 439 in 2022.

As settlements, industry, farming, and infrastructure all expand, elephants will be pushed into ever smaller unconnected pockets of land, forcing them into greater conflict with humans. Unless solutions are found to such conflict, the future for Asian elephants looks bleak. In some countries, like Laos and Nepal, numbers are so small that the trajectory to extinction looks all but certain.