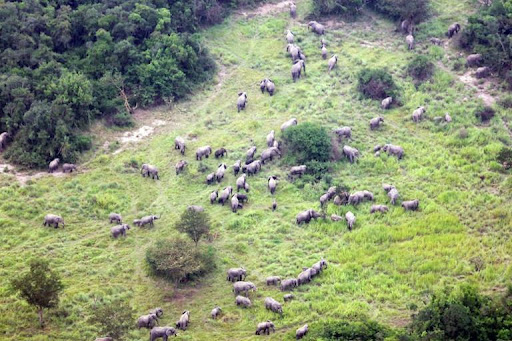

Credit: Mark Hiley

African Elephants

African elephants comprise two species: savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana) and forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis). Millions of elephants once roamed the continent, but in the last 100 years humans have killed around 95% of them for their ivory tusks. Today, savanna elephants are classified as Endangered and forest elephants as Critically Endangered. In 2016 the IUCN estimated a total combined population of 415,000 African elephants left in the world; by 2023 the estimate was around 400,000.

Those that remain face many grave threats to their survival: poaching, which kills around 30,000 elephants each year for their tusks and other body parts; trophy hunting; unregulated killing; the capture and sale of wild elephants (contrary to international law); and the effects of climate change, especially drought. But the biggest threat of all is loss of habitat and the ever-growing conflict with humans caused by this. As human numbers increase and agriculture expands, more forests are lost and the land available to elephants continues to shrink, cutting off their traditional routes and forcing them to seek food elsewhere. This brings them into conflict and competition with humans for fewer resources. They raid farmers’ crops, tear down fences, and enter villages in search of food, causing enormous damage. Casualties of both elephants and humans are more frequent.

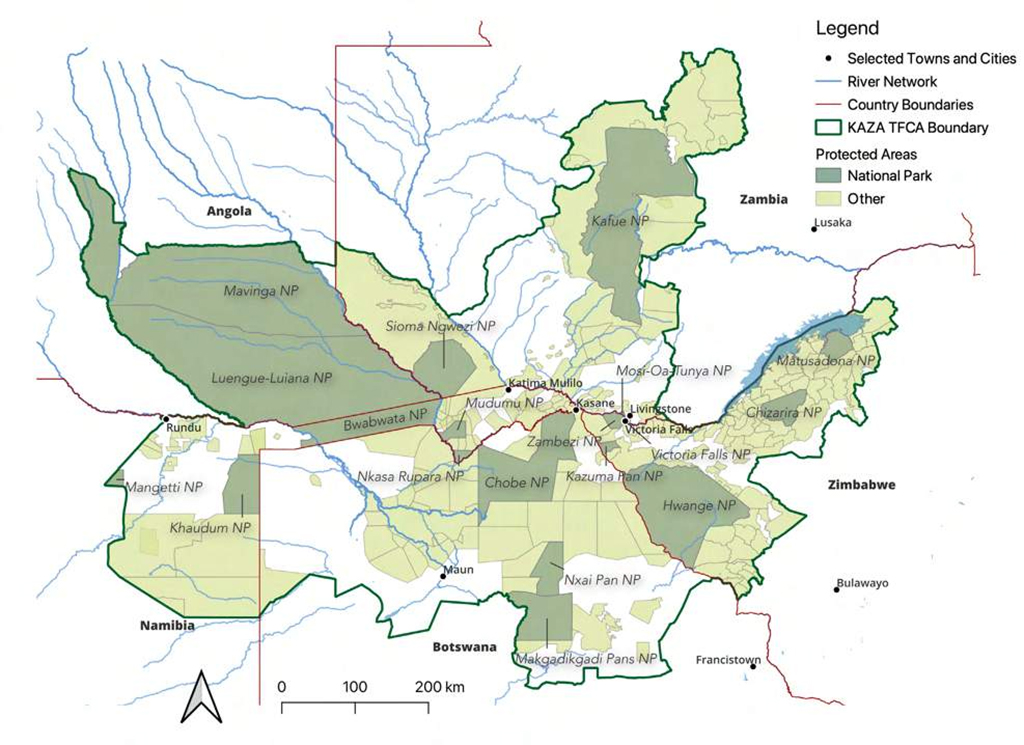

In southern Africa, where most of the world’s remaining savanna elephants are found, the political climate has not been favourable to their survival. The leaders of the countries with the highest elephant populations are less focused on long-term conservation and HEC solutions than on extracting financial gain or political advantage. They resent what they see as foreign interference in how they manage their wildlife (and have threatened to leave CITES), yet are happy to sell hunting licences to foreigners and sell elephants to foreign zoos, as well as use them to curry favour among rural populations, including government-sponsored killings of elephants in areas of conflict with humans). These leaders also want to be allowed to sell their ivory stockpiles and continue to exert pressure for this; in May 2022, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia, Tanzania, and Namibia signed the Hwange Declaration calling to lift the ban on ivory trade – a move that would prove catastrophic for elephants and drive them towards extinction, as it would catalyse a surge in poaching and illegal trade. These five countries are home to an estimated 220,000 elephants in the shared Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), the world’s largest contiguous transboundary elephant population, containing more than half of the total remaining population of this species.

An aerial census of elephants in this region was carried out in Aug-Oct 2022 by Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, with support from WWF and other partners. The goal was to secure baseline data on numbers and distribution to inform effective conservation strategies.

Forest elephants

In 2021, as the result of new research on the population genetics of forest elephants, the IUCN announced that it is a separate species (Loxodonta cyclotis) from the savanna elephant and classed it as Critically Endangered. This status is due to catastrophic population declines of over 86% in around 30 years, mainly due to poaching for their tusks, as well as habitat loss. They have a much slower reproductive rate than savanna elephants, so they cannot bounce back from population declines at the same rate.

Forest elephants are found in the rainforests of central Africa, mainly in Gabon and the Republic of Congo, with smaller, isolated populations in other countries – Cameroon, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Ghana in west Africa. Their habitats in the tropical forests rarely overlap with the range of savanna elephants, which prefer open country and are found in a variety of habitats in Sub-Saharan Africa including grasslands and deserts.

Forest elephants. Credit: Elephant Listening Project

Forest elephants forage on fruit, grasses, seeds, and tree bark; they are referred to as ‘mega-gardeners of the forest’ as they play a crucial role in dispersing plants, including the seeds of large trees which tend to have a high carbon content (the role of elephants in carbon capture is only recently being understood).

The Elephant Listening Project believes that if the decline can be stopped or reversed, forest elephants have the best chance of the elephant species ‘to persist with the full range of behaviors and landscape movements that evolved for survival in their rainforest home. This is because there still are huge expanses of relatively unexploited forest in Central Africa (the second largest tropical forest landscape on earth), and the human population density is relatively sparse and urban. Elephants can move across quite large distances and in East Africa and Asia they are increasingly fenced into protected areas, causing a suite of management problems. Keeping forest elephants roaming freely through Gabon and Congo and Cameroon is our goal.’

Watch the forest elephants of Dzanga Bai.

Rampant Poaching

In 1979 there were 1.3 million elephants left in Africa. Over the following ten years more than half of this population was wiped out to feed the demand for ivory. The scale of this slaughter is hard to comprehend, but it finally led to action with an international ban on ivory trade in 1989.

The ban succeeded in reducing poaching and allowing decimated populations to recover. But the respite was short-lived. The decision by CITES in 1999 to allow so-called ‘one-off’ sales of stockpiled ivory by some African countries to Japan, and again in 2002 and 2008, had the predicted catastrophic consequences. It led to a fresh surge in poaching in which hundreds of thousands more elephants were slaughtered to feed the soaring global demand for ivory.

Carcasses of elephants killed by poachers

Poaching became more sophisticated with the use of military-style weapons. Armed militia in low-flying helicopters mowed down entire herds with AK-47s; rocket-propelled grenades, assault rifles, silencers, and night-vision equipment were all being used in the killing. Deadly poison was used to kill large numbers of elephants and other wildlife which came to drink at waterholes. Spears, traps, snares, poisoned arrows, and bullets were used by villagers as well.

Civil wars and local conflicts

These have also taken a heavy toll on elephant numbers. In South Sudan, decades of civil war reduced the elephant population from over 80,000 in the 1970s to only around 2,000 now (the original estimate of 5,000 was revised). In 2023 war broke out again.

In Gabon, some 11,000 elephants, or 80% of the total population, were killed in less than 10 years between 2004 and 2013. They rebounded later, under President Bongo, but with his ouster in 2023 the future for elephants again looked uncertain.

Elephant poaching also gave rise to security and terrorism concerns across central and eastern African countries. Many poachers and trafficking networks are funded by organised gangs and criminal syndicates with ties to terrorist groups. Armed groups took advantage of high-level corruption and lack of border security to move ivory across borders and avoid detection and prosecution. (The documentary ‘Warlords of Ivory‘ reveals the atrocities committed by an ivory trafficking network coordinated by two of Africa’s most notorious war criminals.)

In West Africa, national parks that spread across remote areas of Benin, Niger, and Burkina Faso and comprise the region’s largest surviving protected wilderness, have become a stronghold for Islamist militants. Pendjari National Park in Benin is a refuge for thousands of elephants, antelopes, and the last few west African cheetahs, and rangers deployed to protect them face conditions of deadly warfare. A spokesperson for African Parks, the organisation which runs Pendjari and the Benin portion of W National Park, fears that if these wilderness areas are lost to militants, ‘then forget conservation in West Africa’.

The close connection between poaching and organised crime also takes a heavy toll on local communities. Rangers are being targeted and killed in growing numbers – over 1,000 in the past decade – while much-needed tourism income is being destroyed.

See China’s Ivory Trade Timeline and UK’s Ivory Trade Timeline.

Beyond the Numbers: Broken Herds, Orphaned Babies

The scale of killing of the past decades led to a collapse not only of elephant numbers but of their family bonds and social structures. With most of the older male bulls already killed, there were no father figures for the sons, which led to young males rampaging and attacking human communities. Poachers then targeted the matriarch of the family – the eldest female member and the core of the family group – who retains all the wisdom, knowledge, and experience that must be passed on to the young, such as where to look for water in times of drought, where to find food, how to look after their young. When the matriarch is killed, the herd must fend for itself without that leadership, leaving it much more vulnerable.

Poachers exploit the tight family bonds of elephants – they shoot a baby first, which causes the herd to gather round to protect it, and then mow down the entire herd. Females, pregnant females, and calves are killed indiscriminately, which means two generations are often extinguished in one murder.

What happens to the babies?

At the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust orphaned baby elephants are rescued and rehabilitated. Credit: DSWT

Like a human infant, an elephant baby cannot survive without the loving care of its mother. Orphaned African elephants have succumbed in droves to starvation, injury, and death through grief. All the elephants that are under 2 years old when their mothers are killed will die unless they are rescued. The over-2’s sometimes survive by befriending other orphans or trying to join another herd that will adopt them, but they are forever traumatised by the horrific killings they have seen and the grief of losing their mother and herd.

Even if calves are rescued, mortality rates are high. The babies are fully dependent on their mother’s milk until they’re 2 years old and are not fully weaned until 4-5 years. Many are so traumatised and grief-stricken by what they’ve witnessed and losing their families that they lose the will to live, and many of them die even with the best care.

Nurturing and caring for these orphans is a slow process that takes years, requiring the utmost devotion and continual care, until they are fully recovered and can be returned to the wild. The chief organisation dedicated to caring for these orphans is the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust.

See Elephants Are Empathetic Beings, a conversation with Daphne Sheldrick.

In March 2021 the IUCN classified savanna elephants as Endangered and forest elephants, a separate species, as Critically Endangered. Without urgently coordinating transnational approaches to saving and protecting Africa’s last elephants, they will vanish from the earth.

Human-elephant Conflict (HEC)

The biggest threat facing wild elephants in both Africa and Asia is habitat loss and conflict with humans. As the human population expands and more land is cleared for agricultural use and development, elephants’ traditional routes and migration corridors become blocked off, confining them to pockets of land and forcing them to seek food elsewhere. This brings them into conflict and competition with humans for fewer resources. They raid farmers’ crops, tear down fences, and enter villages in search of food, causing enormous damage. Casualties of both elephants and humans are more frequent.

For any solutions to HEC to work, they must start with the people living side by side with elephants, as they are the ones losing crops, homes, entire livelihoods, and sometimes family members to elephants. Rather than kill what’s labelled as a ‘problem elephant’ in an area of conflict and give chunks of its meat to villagers, the government should look at ways to bring long-term and sustainable benefits to communities as well as protect the elephants. Coordinated strategies to lift up communities and break the poverty cycle – by providing education, creating jobs, empowering women, enabling small enterprise – are key to stopping poaching.

Beehive fences to deter elephants. Photo courtesy The Elephants & Bees Project/Lucy King

There are many positive developments and initiatives in tackling HEC. In Africa, one very effective solution is the use of beehive fences, which are simple and cheap to make and use only locally sourced materials. They have proved to be very successful; in Kenya where the system was field tested among several communities, it was found to be over 80% successful. The fences reduce crop raids and benefit rural farmers in many ways, including giving them supplementary income from selling honey and bee products.

Human-Elephant Coexistence (HEC) Toolbox

In 2022, Save the Elephants launched a Toolbox of tried and tested elephant deterrents to empower rural communities and reduce human-elephant conflict. It comprises over 80 deterrent strategies, including the successful beehive fence, watch towers, chilli fences, grain stores, and non-palatable crop options. All of the methods have been tested by communities across Africa.

Signs of Recovery

The war in the Democratic Republic of Congo devastated elephant populations, including those in parks and reserves. There are signs of recovery, however; in Virunga National Park, which was decimated by warfare and later Covid-19, a herd of over 500 elephants returned in 2020. With increased security and protection for elephant habitats, it is hoped that the numbers will continue to grow.

Elephants returned to Virunga National Park, DRC, in 2020

In Gabon, thanks to concerted efforts by the environment-friendly president Ali Bongo Ondimba, over the past ten years the country’s elephant population has increased by more than a third to 95,000, or 60-70% of all forest elephants (while over the same period the population in the neighbouring countries fell by 50%). This remarkable turnaround was achieved by a high-powered war on poachers, jailing smugglers, tough pro-environment legislation, and evicting illegal loggers. The strategy also allowed businesses to have land for sustainable activities, and, crucially, the recognition that local people must be compensated for not destroying the forest and encouraged to adopt new farming techniques.

But in recent years there have been growing anti-elephant protests in Gabon by farmers who have seen raids on crops grow worse. Up to 50 elephants are killed each year in self-defence or anger at the crop raiding. The government began rolling out new measures to tackle the problem, with the aim of finding solutions that address human concerns while protecting the elephants. But in Aug 2023 a military coup ousted the president, and there was concern once again for the elephants’ fate.

The Great Elephant Census 2016

In 2016 the first-ever aerial census of Africa’s elephants took place. The Great Elephant Census revealed a shocking decline in elephant numbers beyond the worst expectations. In just seven years, between 2007 and 2014, savanna elephant numbers plummeted by at least 30% – around 144,000 elephants were killed.

Specific areas fared even worse: in Tanzania’s Selous Game Reserve and in Mozambique’s Niassa Reserve, elephant populations fell by over 75% in this period, as poachers wiped out entire herds at a time.

The survey counted a total of 352,271 elephants in the 18 countries surveyed (Namibia chose to be excluded). This figure represents at least 93% of savanna elephants in these countries.

Around 84% of the populations surveyed were in legally protected areas while 16% were in unprotected areas. However, high numbers of elephant carcasses were discovered in many protected areas, indicating that elephants are struggling both inside and outside parks.

The census concluded that the rate of species decline was 8% per year, primarily due to poaching (with a greater decline from 2007 to 2014). At this rate, it was estimated that elephant numbers could halve in nine years if nothing changed, and localised extinctions were sure to accelerate.

The greatest declines were in Tanzania and Mozambique, with a combined loss to poaching of 73,000 elephants in just five years. Another shocking discovery was made in northern Cameroon, where survey teams counted no more than 148 elephants – along with many carcasses – revealing a tiny regional population in immediate danger of extinction.

By contrast, South Africa, Uganda, parts of Malawi and Kenya, and the W-Arli-Pendjari conservation complex – the only area in West Africa with significant numbers of savanna elephants – were found to have stable or slightly growing herds.

In 2016 Botswana was still the continent’s elephant stronghold, with 130,000 elephants, concentrated along the Chobe and Savuti river systems in the north and in the vast wetland oasis of the Okavango Delta. Botswana was the sole hunting-free haven for elephants under President Khama, but that all changed with the new regime in 2019 under President Masisi, which allowed trophy hunting.

Zimbabwe showed the second highest number of elephants – 83,000 – mostly along the Zambezi River and in Hwange National Park. Overall, Zimbabwe’s population has dropped 10% since 2005.

Zambia recorded 20,839 elephants, an 11% decline during the past decade. But a regional population in the southwestern corner of the country has been even worse hit by poaching: researchers counted just 48 elephants in Sioma Ngwezi National Park, down from 900 in 2004. At the current poaching rate, this local population also faces imminent extirpation.

Angola too gave a shock. Once hoped to be a refuge for elephants after decades of civil war, it now had one of the highest poaching rates on the continent, leading to a 22% drop in elephant numbers since 2005.

Namibia was the only country with a significant elephant population that chose not to participate in the census. The official figure of 23,736 elephants (2020) is disputed, as conservationists estimate that between 17,265 (73%) and 20,000 (84%) are migratory elephants that move across borders between Namibia, Angola, Zambia and Botswana; that model leaves an actual resident population in Namibia of only 5,688.

In 2021 the government announced it would auction off 170 wild-caught elephants, a move that earned global condemnation; in the end it auctioned 57, 22 of which were sent to Abu Dhabi to live out their lives in wretched captivity. The captures and sales contravened international law and provoked outrage, but no punitive action was taken against the Namibian government.

KAZA Aerial Survey 2022

The Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA) is home to more than half of the remaining savanna elephants in Africa. In Aug-Oct 2022 an aerial survey of their populations took place. It was the first time that all five KAZA states – Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe – along with multiple organisations, governments, and partners, undertook a collaborative, synchronised survey of the entire contiguous elephant population. This was seen as particularly important in KAZA, a vast transboundary conservation area where elephants and other wildlife move regularly across country borders (the 2016 census was based on results from separate country surveys, which, it was claimed by the KAZA survey, skewed the figures).

Overall, the survey’s conclusion that elephant populations in the region were ‘stable’ was greeted as positive news. But the very high mortality rate, seen in the high carcass ratio – a critical measure of the health of populations – was worrying, and called for further investigation.

The survey showed growing fragmentation and isolation of wildlife habitat. ‘This fragmentation due to encroachment of human and livestock activity affects the connectivity and mobility of wildlife populations, making the ecosystem “vulnerable to disturbances and less able to adapt to changing climatic conditions”, said the report. There was also a trend of elephants being absent from regions heavily populated by humans and livestock. The survey revealed notably high pressure in the central Zambezi region of Namibia. This region, covering the Kwando and Zambezi-Chobe Wildlife Dispersal Areas, is critical for wildlife movement and migration. The distribution of elephants showed a higher density of elephants near permanent water sources such as the Okavango and Chobe-Linyanti-Kwando River systems, as well as in parts of northwestern Matabeleland (Zimbabwe), where artificial water supplies are widely available in Hwange National Park’ (Africa Geographic, KAZA’s elephant survey – the results are in).

The estimated total population for the KAZA region was 227,900 (+/-16,743), with slight increases noted in Zimbabwe (65,028), Botswana (131,909), Namibia (21,090), and Angola (5,983), and a decrease in Zambia (3,840).

The indications of a stable population for KAZA’s elephants are encouraging, but the key will lie in how this information is applied to conservation efforts in the five countries. Will it translate into policies and actions on the ground, and will these be implemented by the respective leaders across the KAZA region? As the human population expands, elephant habitats and the routes connecting them will need ever-greater protection, as will communities living with elephants, and it’s hoped that the survey results will enable these challenges to be addressed more effectively.

Map of the KAZA area, showing national parks and other protected areas. Credit: KAZA TFCA (Secretariat) 2023

Credit: Mark Hiley